Japan trying to liberalize immigration to fight deflation — a fact US should take note of.

By Krishnakumar S.

Thus inflation is unjust and deflation is inexpedient. Of the two things deflation is, if we rule out the exaggerated inflations such as that of Germany, the worse, because it is worse, in an impoverished world, to provoke unemployment than to disappoint the rentier. — John Maynard Keynes, “Essays in Persuasion,” (1933)

Deflation has been with the Japanese economy for the last twenty-five years. No wonder, it has been considered to be synonymous with Japan. Indeed, during 1995-2007, Japan witnessed a decrease in the nominal GDP from $5.33 trillion to $4.36 trillion. Japan experienced the specter of deflation since the 1990s — much before the rest of the world began experiencing it.

In fact, the last two and half decades were lost decades of growth for Japan. Prior to that, one used to hear stories of the techno whiz kids of Tokyo readying to upstage the United States. Everything about Japan in the mid eighties gave the world a new sense of prosperity, automobiles and electronics and all that.

The whiz kids of Tokyo, it was told, were all set to drive United States out of business. Elsewhere in the world, people were mesmerized by the stories of the rise of Japan. The pink press celebrated the Nikkei reaching the stratospheric levels of 38,000 plus and the land prices in Tokyo being the highest in the world. But come 1990s, all that came tumbling down, crashing to lows, from which they are yet to recover.

Since 2012, it has been a do-or-die battle for Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and his government against deflation. The determined efforts since 2012 were further reinvigorated following his re-election in 2014, with the prime minister putting in place the three-arrow strategy of monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reform.

Signs of success are showing up, as various reports from Japan indicate. If true, this would be a game-changer for the world, as well as for the Japanese economy. Is the three-arrow strategy delivering Japan out of the pool of deflation? Will it push the country to be a $6 trillion economy by 2022, as projected by the policymakers?

The three-arrow strategy is distinctly different from the ones pursued by several other countries, whose focus has been heavily centered on monetary stimulus. Even when Janet Yellen and other central bankers had initiated talks on the possibilities of tapering bond purchases in 2013, and the world was witness to the taper tantrums taking its toll of the emerging market economies, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda and others were busy expanding bond purchases on an unprecedented scale.

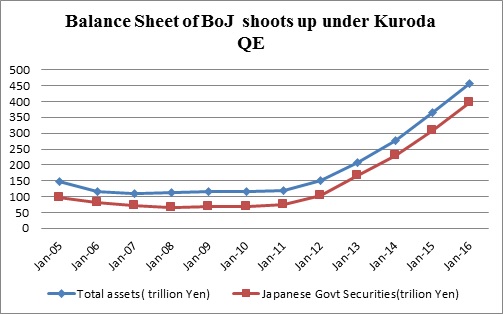

Indeed the data released recently by the Bank of Japan reveals that at the end of September 2016, it had held a total of 457.2 trillion yen in assets, of which Japanese government securities accounted for 397.6 trillion yen. This is far higher compared to 144.9 trillion yen of assets and 102.9 trillion yen in Japanese Government Securities in September 2012. (See Chart below.) In fact, the assets of the Bank of Japan are as high as 80% of the GDP. Despite the large monetary stimulus under the unconventional monetary policies, the assets of the central banks in US, as well as ECB, runs to at best 25% of their respective GDPs.

In fact, what makes the Japanese policy experiment distinctly different from both their US and European Union counterparts is that the quantitative easing strategies pursued on the monetary policy front is coupled with huge fiscal upscaling, notwithstanding the trenchant criticism from austerity pundits on the fallout of the growing public debt. Rather than going all out against the recession, the Americans were half-way deliberating on the debt ceiling limit. Worse are the Europeans, whose governments have given up on their autonomy over fiscal policies by being part of the Union.

Years of wading through the waters of deflation have given the Japanese leaders the force and authority to prevail over the fiscal orthodoxy that public spending is not a bad thing to do during times of recession. Even when they are trying to moderate the level of fiscal expansion, they would like to have a sustained rate of growth in the economy, which would catapult Japan to 600 trillion yen economy by 2022.

Indeed in the 2016 budget, Abe’s government has allocated expenditure to the tune of 51.1 billion yen to build more childcare facilities, 136.6 billion yen to provide more senior housing and nursing care, and cash stipends of 30,000 yen to 11 million to low-income pensioners. This is apart from the reduction in corporate tax rate from 32.11% to 29.97%.

Indeed Japan is trying to address its issues of rampant conservatism through policies favoring better employment rules for women through structural reform of its labor markets. Despite being a large advanced country, Japan has a very low labor force participation among women, and too low a foreign worker participation rate. Liberal leaves for maternity, child care as well as care for old age is being worked out. Immigration rules are also being relaxed.

Now these strategies seem to be delivering results. Though Japan would like to have a 2% rate of inflation, at least, it has entered into the positive terrain of inflation. Though the Nikkei had reached the stratospheric levels of near 38,957.44 in December 1989, and the Japanese would like to forget about the crash ever since, which resulted in two lost decades, in the previous year, it had peaked to a 18-year high at 20,000 plus , largely due to the monetary easing policies. But even as asset price bubbles have had the favorable effect on bolstering demand, Japanese should know better about the volatility and catastrophic risks associated with the same. Finally, the policies of the Abe-Kuroda duo seem to be delivering at last.

But it is yet to be seen as to whether the plan of increasing the fertility rate in Japan from 1.4 to 1.8 births per women would work. Perhaps the only way the labor shortages in Japan can be met is by pursuing a far more liberal immigrant policy, as outlined in its structural reforms.

In this case, the United States, which is now thinking of restricting immigration should know that there is lots at stake here. Every innovation and patent registered in the recent decades in US has a slice of direct or indirect immigrant presence in it. Indeed the Silicon Valley would not have been possible without immigrants. Most of the new American Nobel laureates are one-time immigrants. And now, when Japan is looking for immigrants, and it is sure that Abe is going to welcome them, much is at stake, for United States, too, in this game.

(Krishnakumar S. teaches economics at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, New Delhi.)

More from Krishnakumar S.:

Chinese to benefit from US-India showdown over solar panels at WTO (September 23, 2016)

With Brexit, is it going to be a season of referendums in Europe? (June 24, 2016)

Raghuram Rajan’s exit provides more fodder to the volatile financial markets (June 20, 2016)

Will writings based on Gods and Goddesses continue in India? (October 21, 2015)

Yanis Varoufakis is Keynes of our generation (July 7, 2015)

Will Modi’s plan to channelize gold holdings from temples to banking system succeed?(May 8, 2015)

All eyes on Yellen, as global markets brace for reversal in US monetary policy (March 21, 2015)

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank – Are the Bretton Wood twins being dislodged?(March 17, 2015)

Are the political duopolists in New Delhi colluding? (December 19, 2012)

1 Comment

Japan is only looking to import high end labor, and even then it helps if you have Japanese ancestry. They don’t want illegal labor or low end labor.