An interview with Vappala Balachandran, author of The Secret Story of ACN Nambiar, a biography of the late freedom fighter and head of “Indian Legion.”

Vappala Balachandran, a former intelligence officer and security analyst, was a Special Secretary at Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India. He had led the Indian inter-agency teams for annual dialogue with US agencies on terrorism. He was also a member of the two-member high level committee which inquired into the Mumbai 26/11 terror attacks.

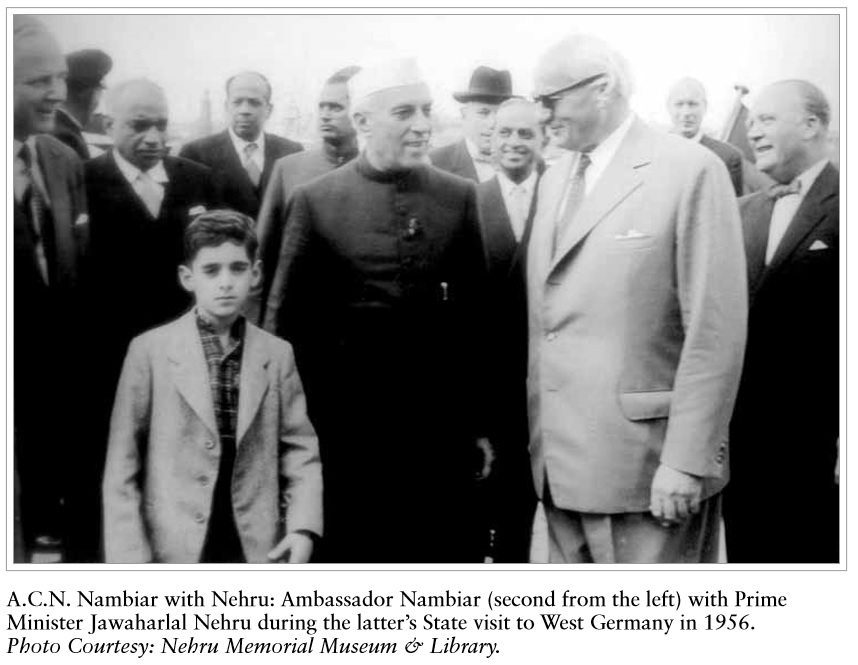

In his latest book, A life in Shadow: The Secret Story of ACN Nambiar, Balachandran provides a rare insight on Nambiar, a freedom fighter, journalist, confidante of Jawaharlal Nehru, trusted team member of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s inner circle and a former Indian Ambassador to Germany.

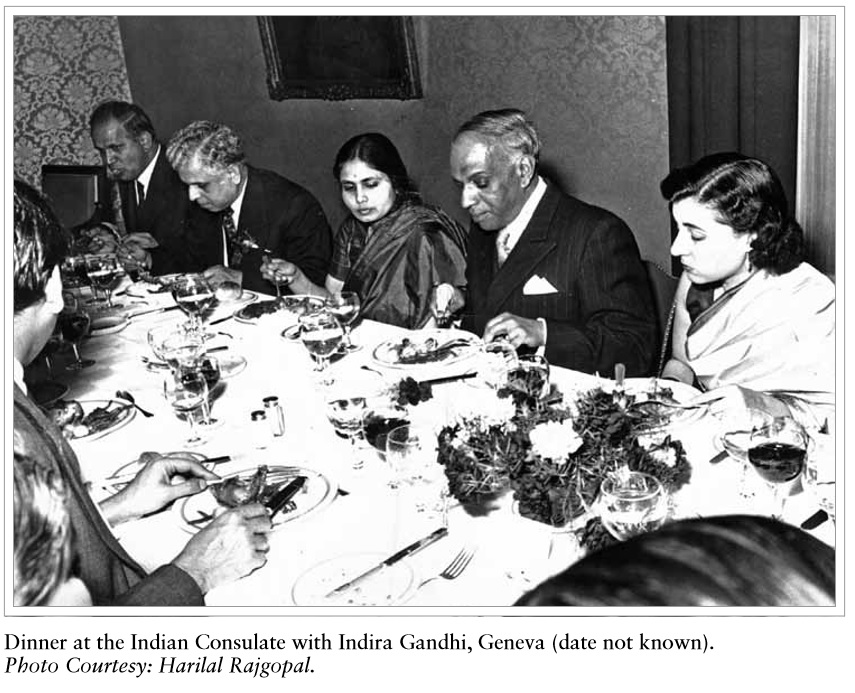

The book contains several anecdotes that were never revealed to public earlier. For instance, Motilal Nehru and Jawaharlal Nehru’s views on key contemporary issues, Jawaharlal Nehru’s health consciousness, Bose’s fears during India’s freedom struggle, the Nazi obsession to crack Indian freedom fighters during World War II, Indians who struggled abroad to ensure motherland’s independence, Indra Gandhi’s affection for Nambiar, Rajeev Gandhi response to former Prime Minister’s assassination and many more.

A life in Shadow provides a rare insight into the mind of Nambiar — who’s affectionately called Nanu. Readers would find it a delightful peep into the mind of someone who rubbed shoulders with world’s who’s who.

Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had assigned Balachandran to assist Nambiar in his later years. The assignment made Balachandran one of the very few people who spent considerable time with Nambiar in his last years. He went into depression after the former prime minister’s assassination in 1984.

In a freewheeling interview with The American Bazaar, Balachandran discusses the book.

What was the inspiration behind the book?

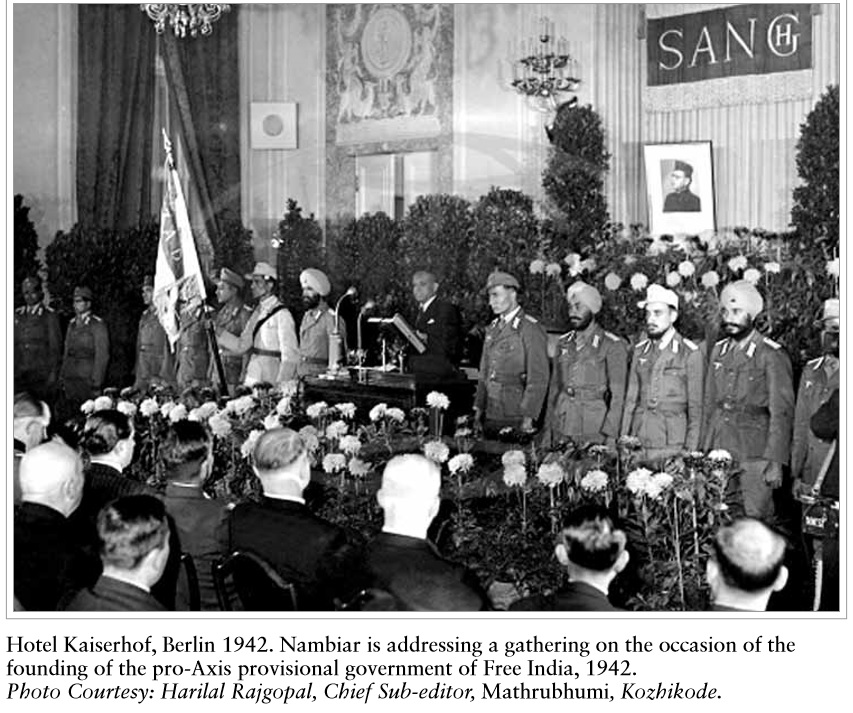

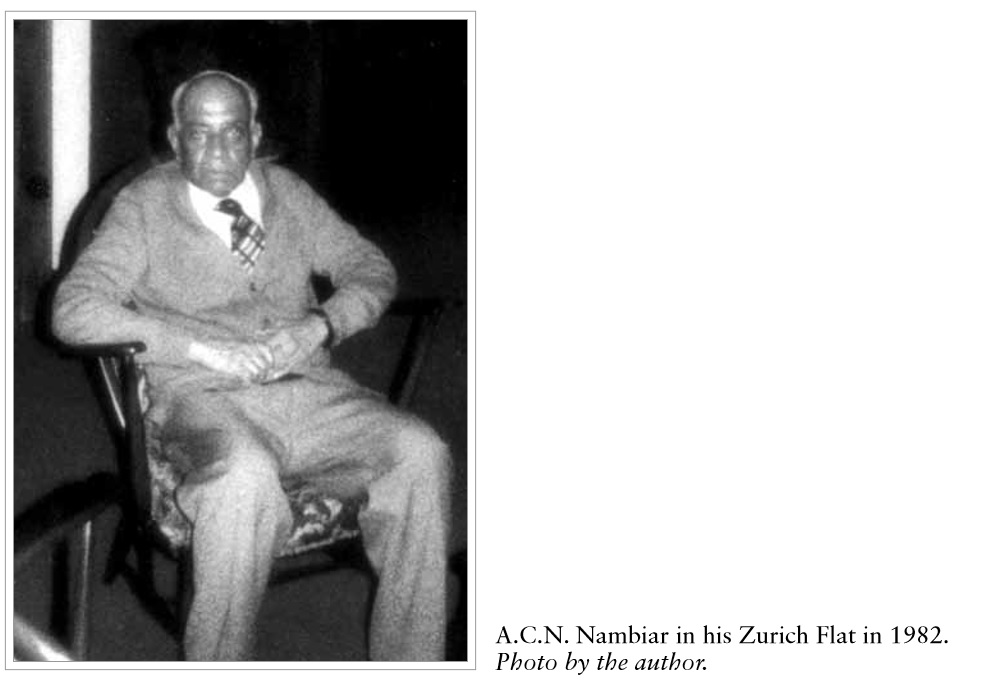

In 2001, I read a book written by a German writer named Rudolf Hartog about the “Indian Legion” in Nazi Germany raised by Subhas Chandra Bose as his future Indian Army. Hartog was the interpreter in the Legion for the German trainers and the Indian members of the Legion. It gave vivid details how the Legion was run as a disciplined army, although all trainees were Indian POWs (Prisoners of War) captured by Germany. I was rather surprised to know that Mr. Nambiar was the main person administering this 4,000-strong army. That gave a new dimension to Mr. Nambiar’s life story which I did not know earlier, although I was meeting him regularly between 1980 (when I first met him) and 1986 (the year of his death). During our regular meetings, first at Zurich and later in Delhi, Nambiar did not tell me all these details except that he had worked for Bose. Hence I decided to investigate further. I came across startling details during my long research into his life first by reading published literature and then scouring through declassified secret intelligence records.

What were your initial impressions of Nambiar? It started as an assignment, but developed into a close bond.

When I first met him in 1980 he was 84. I was 43. Despite this age difference, he was very polite and friendly although he could have ordered me around since he was on first name basis with Jawaharlal Nehru and Mrs. Indira Gandhi, who was then the Prime Minister. He exhibited no arrogance despite knowing that I was a middle level officer who was assigned this work as part of my duty. On the other hand, he was unfailingly courteous, always inquiring about my comforts. At the same time, he was a treasure trove of information on European history, governance, security and power play of nations from the 1920s to the 1980s. This helped me in learning more about the turbulent history of that region.

You were one of the very few people who spent considerable time with the late patriot and freedom fighter. Tell us more about him…

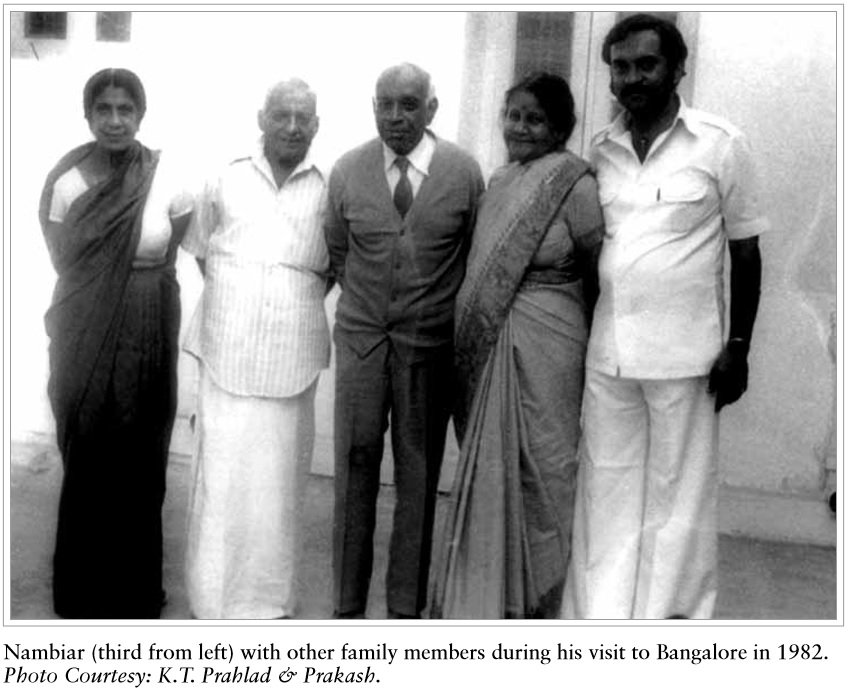

Having exiled himself from India from 1919, due to various personal reasons, he had no family affiliations. Despite this he trusted me and treated me as a member of his family. He wanted me to do all his errands like accompanying him twice to India from Zurich and caring for his living arrangements including medical care in Delhi.

You mention that Nambiar never revealed his close association with Subhas Chandra Bose to you. Why?

He did mention that he was a close associate of Bose and had also earned his trust. But he did not tell me vividly all the important assignments he undertook for Bose like manning the Free India Center, administering the India Legion and doing propaganda work against British India, for which ultimately he was imprisoned by Britain for a long period. I don’t know why he did not tell me these details. Perhaps that was a painful period in his life. In fact in retrospect, after completing this book, I find that many aspects of his long life, including his separation from his wife, were not divulged to me. Nor did I ask him any details of his personal life as it would have been impolite as I was on duty to look after a national hero respected by the then Prime Minister.

Nambiar once saw Adolf Hitler. What were his thoughts on the Nazi dictator?

He did not tell me his impressions on Hitler except in general terms and that he had accompanied Bose to meet him. I learnt details of this meeting only from Hartog’s book after 2001.

Interestingly, Nambiar had good equation with both Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose. Both leaders had different thoughts on India’s independence.

His relationship with Nehru was on a different keel. In fact, he always used to compare and contrast his relationship with Nehru and Bose by saying that his relationship with Nehru was personal, while that with Bose was political and official. Bose was a formal person, while Nehru was playful and friendly with him. Details of this relationship are given in Epilogue.

You mention about Nambiar personal turbulence. Could you elaborate?

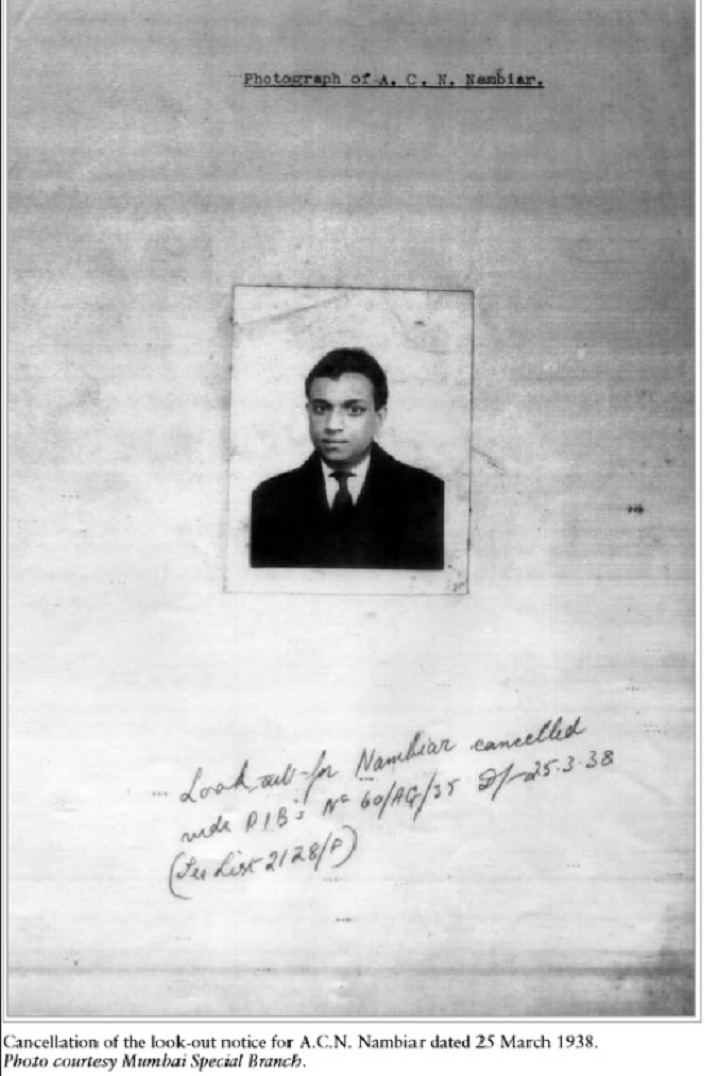

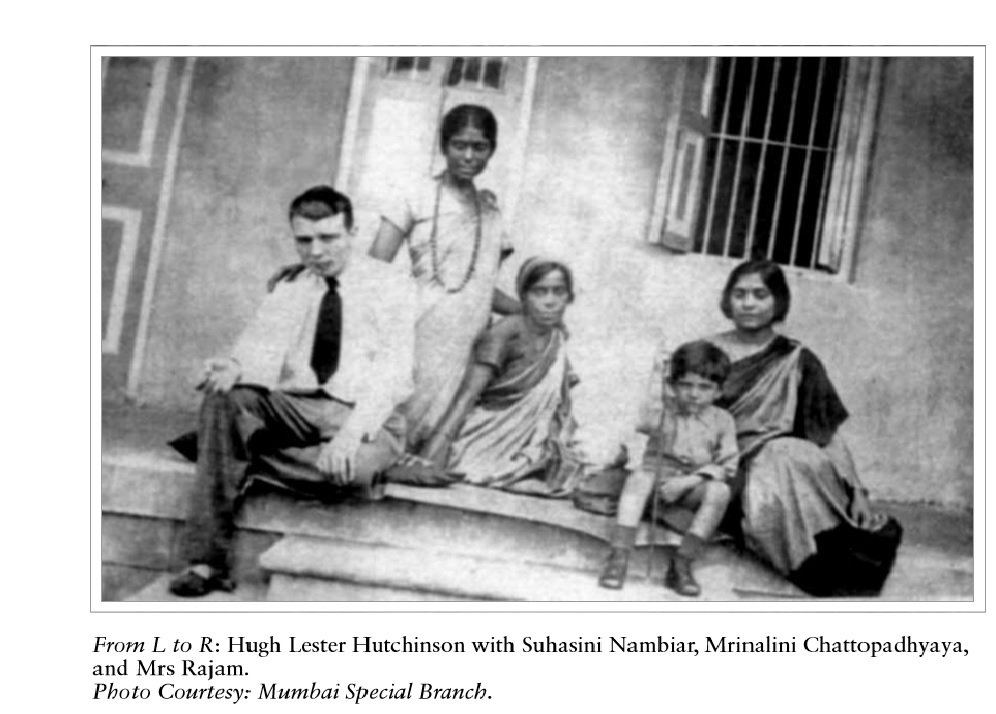

First he quarreled with his elder brother over his marriage with Suhasini. In that process, he distanced himself away from his family and exiled to Europe. He cut himself away from his family in India. Secondly, he had an unhappy married life. He had told me that his wife, Suhasini, had broken away from him on ideological grounds as she wanted to pursue a full time Communist life. However, while researching into his life, I found that it was he who was, in fact, partly responsible for this unhappy married life by keeping Suhasini away in India, while living with a German woman. This I discovered only from the secret Bombay Special Branch records in 2009. As a biographer, I had to record the truth despite my personal affinity and loyalty towards him. However, I should emphatically record here that his personal dalliance did not affect my esteem for him or in any way temper the magnitude and importance of his work as a freedom fighter from Europe.

Tell us more about Nambiar’s role in India’s independence…

The journalist’s life in Berlin gave Nambiar access to various personalities living or transiting through Europe. He helped raise awareness in India and European colonial exploitation through his columns. He could closely interact with Conservatives, Socialists and Communists who were struggling to gain prominence in Germany and Europe. More particularly, he could watch, report and help the struggle for Indian independence launched from Europe and enlighten Indian domestic audience about such developments. In 1929, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was the General Secretary of the Indian National Congress, asked Nambiar to establish an “Indian Information Bureau” as the official face of Indian anti-imperialism in Germany for attending to the needs of Indian students in Germany and for facilitating their practical training in Germany. Later he joined Subhas Chandra Bose in 1942 in establishing the “Free India Center” (Azad Hind Office) and liaising with the German Foreign office for making radio broadcasts, issuing bulletins, publishing a monthly magazine, holding discussions on developments in free India and attending to the newly founded “Indian Legion” — a military force raised to liberate India from the British.

Nambiar had six siblings. Only one finds a mention in the book. Please elaborate.

Others were not important to the Nambiar story. I have mentioned Madhavan, his elder brother who caused strains in their relationship by admonishing Nanu for marrying Suhasini. I have also mentioned another brother Major Gopalan Nambiar, who called Madhavan “the despicable Candeth” in a letter to Nanu dated August 23, 1929. This letter was censored by Bombay Special Branch as Nanu was under watch by the British-India government.

Suhasini Chattopadhyaya, Nambiar’s wife and youngest sister of poet and politician Sarojini Naidu, was an accomplished figure. Could you share any insights on her?

Suhasini Chattopadhyaya was woman of many talents. She was also “a woman of striking beauty” as Agnes Smedley, her brother Chatto’s then-wife, recalled in her book The Battle Hymn of China. John Maxwell Hamilton, biographer of veteran American journalist Edgar Snow, quoted him saying that Suhasini, who hosted Snow during his visit to Bombay in the 1930s, was “the most beautiful woman” he had ever met. In Bombay, she took active part in agitational politics by organizing assistance to those arrested in the “Meerut Conspiracy Case,” staging plays, dance and drama for social awareness and publishing The New Spark for the Communist Party. As a result she continued to be under watch throughout this period. She was fond of fine arts and raised “The Little Ballet Group” and “Indian Peoples’ Theater” in Bombay. However, after some years she could not take very active part in agitational activities due to her delicate health. Yet she belonged to the old breed of Communists who could not fit into the new style of Communist leaders who emerged during the 1960s and 70s.

Nambiar and Suhasini made quite an unusual couple. Tell us more about their relationship.

It was clear that Nambiar and Suhasini were really not made for each other. The marriage was bound to break up. Nambiar preferred to be a low profile leftist journalist, who tried to use his pen to agitate against colonial exploitation. The only active movement he undertook against the British Empire was from 1942 when he was compelled to join Bose in Berlin, although he had serious misgivings whether it would succeed. Please see the chapter “The reluctant right-hand man.” Suhasini, on the other hand, was the first woman member of the Communist Party of India. She was intellectually radicalized very early, aligning herself more with the agitationists who believed in the use of violent, subversive means towards freedom. It was fortuitous that she was sent to India by the Comintern to whip up agitational activities, while Nambiar who stayed behind in Berlin developed liaison with Eva Geissler. And Nambiar did not allow Suhasini to join him in Berlin.

Nambiar had a large family, but no one came to claim his “rich” belongings. Why?

When he died, Nambiar had only modest cash savings with him at home and in the bank indicating how hard his life must have been in Europe. Even the British intelligence records had said that he was eking out his living. However, he left behind some valuable mementos, clothes, crockery and books. He did not leave behind “rich” belongings. His relatives in India wanted to be on the right side of the law. They did not know whether Nambiar who was away from India since 1919 had any legal heirs abroad. Perhaps their reluctance in claiming his belongings was justified when a few months after his death the Prime Minister received a letter from a Swiss national named Christoph Struchen claiming that he was Nanu’s son through a lady named Bertha in Zurich. He staked a claim over his savings and belongings. Bertha was Nanu’s housekeeper in Zurich and Christoph had driven him to Geneva airport twice when Nanu returned to India. We requested the PM’s office to reply to Christoph that he should make his claim through legal means. Nothing was further heard about this request.

Did Nambiar ever plan to author a book?

Nambiar did not want to write any book. He said that he was too old. He went into a deep depression after Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984. In order to divert his attention I tried to persuade him to write his memoirs. He politely declined on account of poor health. Ultimately, I could succeed in making him dictate his story to a Dictaphone, which was transcribed by my staff on his small typewriter. The pages were corrected by him. Yet, details in his memoirs (the Oral Transcripts – OT) as dictated by him were very sketchy – particularly with regard to his personal life and the important role he played as Bose’s right-hand man during the turbulent Second World War period.

Your book is an interesting amalgamation of youth, ambition, family, romance, patriotism and struggle. It can be a good subject for a documentary or a feature film, too. Any plans or offers?

Nothing of the sort now. My publishers have to decide if such a proposal is made out.

You are a former intelligence officer and security analyst. You were a Special Secretary at Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India. Could you share your experience?

I joined the national intelligence service only in 1976 after 17 years in the police. My experience since 1976 till my retirement in 1995 had been on preserving our national integrity and security from various challenges by collecting advance intelligence. All I can say is that our national intelligence services have been more than equal in facing these threats.

1 Comment

The interview is very much informative.As an independent researcher on the rise and fall of the Communist movement in India,I was following the political life of Suhasini.I am much impressed by Vappala’s observations.