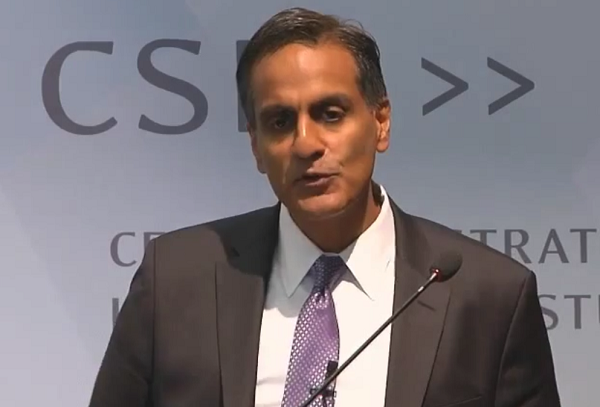

Former U.S. ambassador to India Rich Verma says U.S.-India relations are a non-partisan issue” and a Biden administration treat India “as an equal partner.”

Richard Rahul Verma is the first and only Indian American to serve as U.S. Ambassador to India. He served as America’s top envoy in New Delhi from December 2014 to January 2017. During President Barack Obama’s first term, Verma served as the Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs at the U.S. Department of State.

Son of an English professor and special education teacher mother, who came to the United States in the 1960s, Verma earned his bachelor’s degree from Lehigh University, LLM from the Georgetown University Law Center (LLM), and JD from American University’s Washington College of Law (JD).

He is a Centennial Fellow at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service and a Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

In a recent interview with Frank Islam, Verma spoke about the future of U.S.-India relations and the contributions of Indian Americans, among other topics. The interview was originally streamed by the South Asia Monitor. It has been edited for clarity.

How high do you think South Asia will figure in American foreign policy under a Biden administration? Also what will be the compelling case for the U.S. to have a continued engagement with South Asia? When I say South Asia I want you to focus on India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, and talk about the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan as well.

Sure. It’s a great question. I really hope we can return South Asia to a place of prominence in our foreign policy. That’s where it should be. I regret to say that it has not been a priority for this administration. For example, we’ve gone the entire term without a Senate-confirmed assistant secretary of state for South Asia. Can you can you imagine that? We have terrific career people, but no presidential appointee to speak for the president. I think that’s been noticed. And unfortunately, again, we’ve been mired in kind of these small trade skirmishes with India after imposing tariffs on them and revoking their trade privilege status. And that seems to have been the focus of our efforts in South Asia. The USTR, [United States Trade Representative] has dominated our discourse, and I just don’t understand why.

Now, when we think about South Asia, a lot of challenges — security challenges, development challenges — but we also think of South Asia as a place of incredible promise: a youth dividend, a demographic dividend; urbanization taking place at rapid rates; innovation, discovery, startups, incredible educational attainment, infrastructure development. If you just look at what’s going on in the region, it’s becoming more integrated. And that’s reason to be hopeful, but we have to be a partner in that exercise — not looking down, not lecturing not from the outside, but really being an equal partner. And I do think a Biden administration will do that. We don’t have to guess; you can look at a 40-year record at how Joe Biden has focused on South Asia, worked on South Asia and we can talk more about that. But I’ve seen him firsthand do that.

What are the fundamental and ideological differences in the public and Democratic administration approaches to India and Pakistan. I’ll be more interested, if you can shed some bright lights on the immigration, defense, climate change, terrorism, Russia, Iran, China and North Korea, and commerce, trade, and investment. And also promoting our democratic values, which is freedom press, freedom of faith and respect for human rights?

I think there used to be a somewhat bipartisan position towards India and Pakistan. I think it’s important to go back in our history here — towards the tail end of the Clinton administration, around 1998-1999. After the Kargil crisis, President Clinton made a very determined decision to separate our India policy from our Pakistan policy. He de-linked, or de-hyphenated them, and I think that was exactly the right thing to do. Both were very important countries. But we shouldn’t be balancing India off Pakistan and Pakistan off India. I think that was the start of this effort to pursue independent policies. Of course, we were worried about the balance of power in Asia. And that meant concerns about a rising China. There was focus on security; and regrettably terrorism increasing in the region, problems with cross-border terrorism. So from Clinton to [President George W.] Bush to [President] Obama, and I would even say, into the first year of the Trump administration, there was a continuity. There was a continuity again about the need for peace and security, particularly in Afghanistan. The need for the people of Pakistan to live peacefully, and not have the military and intelligence apparatus dominate their lives. There was a recognition that India would be the defining partnership for the United States in this century. There was an increasing role, the importance of Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka. Really this is what I mean when South Asia was so important. And of course, as I said, we were concerned about losing ground to democracy. We were concerned about countervailing pressures that Russia and China were placing. So look, this is a critically important area. And I hope… I know there is a bipartisan interest in supporting South Asia… Pakistan. But we’ve kind of lost the thread. I hate to say we’ve lost the thread. The one area where we have seen some continuity is in the defense side. I give a lot of credit to Pacific Command. This notion of Joint Strategic Vision for South Asia and the Indo-Pacific that President Bush talked about, then President Obama talked about, is now the free and open Indo-Pacific strategy. The Quad is an important part of that. And again India is a cornerstone of that. So that has been one area of continuity. But we have to build all the elements of our cooperation, all of them.

What do you think that Afghan peace movement that’s taking place, and the withdrawal of United States troops from Afghanistan? What’re your thoughts on that?

It’s a very difficult situation. There’re a lot of factors: one U.S. forces have been there for nearly 20 years now. I think people are tired and they want they want to be able to draw down. But we also have an incredibly important security interest in that region, and we have a friend and partner in a democratically elected Afghan government that we want to succeed. There’s an exceptional amount of concern about giving the Taliban a seat at the table — power sharing. We’re not the only ones with that concern. India has a significant concern. And there is a lot of focus on the role that Pakistan will play. Will they play a helpful role? Will they play a kind of more of a spoiler role? I’m hopeful that they see the interest in an Afghanistan that is peaceful and that is governed by its own people as well. So it’s critically important and the next president — whoever that is — is really going to have to see this through, again with strong partners in the region. India has played a huge role here providing nearly four or five billion dollars in development aid, some military assistance, in training and equipment. The most important thing is that the people of Afghanistan get to live freely and peacefully without interference from outside players.

What makes Indian Americans so special and what’s the reason for their growing profile and their importance of influence in spite of their relatively small numbers compared to many other communities? They have helped shape the United States. Indian Americans are considered a model minority.

Well, Frank, you’re the uh you’re the epitome of that story.

Thank you very much. You are too, ambassador.

Well, I don’t know. I had a lot of people in front of me doing a lot of hard work, including my mom and dad, who gave me every opportunity. The story of South Asian and Indian American immigration to the United States is a fascinating story. We don’t have generations of it, we just have a generation or two. Not that long of a story. My dad came over in 1963. He was on the early side. Now I know we had people earlier and they went to California, and did a lot of hard work. But really the brunt of the people came in the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s. And they just put their heads down. They came here to give their family a better way of life, a hope for a better future. What was interesting is that we kind of joke: they just wanted their kids to become doctors and engineers and scientists, stay out of this public life, stay out of this civic life. Because they were so worried about just kind of getting their feet underneath them, getting assimilated, retaining all the great things of their culture. But they didn’t want their kids necessarily to be caught up in civic engagement. That has changed; changed dramatically. Despite every protestation of my parents, I never made it to medical school. I started a career in the military, worked on Capitol Hill. I was kind of bucking the tradition. When I worked on Capitol Hill in the late ’80s and early ’90s, I could count on one hand the number of Indian American staffers in the House and Senate. Now we have five Indian American members of Congress. We have an Indian American on the presidential ticket, as vice president. So this has turned on its head, thankfully. And then the number of Indian Americans I see not only in public, in kind of the public positions, but in civil society, in nonprofits, in academia, at every place in American life, I’m really heartened by that.

But I think though the one thing I would say is that I do think we have to be careful about assuming that all of us are in the top one percent, that all of us have made it. This Covid crisis has really brought out some of the real pain and anguish and struggle. For example, there’s a lot of us living on the margins. There’s a lot of businesses that did not make it. There’s a lot of hotels and restaurants that will not make it. There’s a lot of new immigrants who are really struggling. I don’t want to be too negative, unfortunately there is this kind of anti-immigrant backlash that politicians are using for political purpose. A lot of people are scared, so they blame the immigrants. They blame the immigrants for their economic situation, or their health situation. We really have to push back and fight back against that with everything we can.

Before I go to my next question, I wanted to say that I gave a speech at the JFK Library not too long ago. It was an immigration naturalization ceremony, and I quoted [President Kennedy] —“immigrants feed this nation with horizons a new frontier thereby keeping the hope alive.” That’s President Kennedy’s quote. He took a lot of pride in the fact that his ancestors came during the potato famine from Ireland.

It’s interesting you mentioned President Kennedy. He was not with us long enough, and he was not president long enough. But when I think about his impact, for example, on just minority communities, and, frankly, U.S.-India relations, I think you know it’s still a bit of an untold story about how strongly he felt about India, from the time he was a senator, through the time he was president.

Very well said. We talked about the Indian diaspora. Let’s talk about what Indian diaspora can do to help India achieve its fullest potential. They have the character, they have capacity and they have competence to make a difference. And they have made a substantial contribution in people to people engagement, innovation, entrepreneurship, education, commerce, investment and creating companies. What can they do, in terms of, providing a capital for startup companies, creating jobs in India? What are the things they can do to help India?

Let me let me take a step back first and just talk about what brings two countries together. You have presidents and prime ministers that can have summits and you can have formal engagements in Washington, New Delhi, Islamabad [and] Dhaka. Right? But you know presidents and prime ministers come and go. Governments come and go. The glue that actually holds countries together are really two things. They are the values that we share together and they are the people that come back and forth, that migrate back and forth, that travel back and forth, that do business back and forth. That is the actual glue that brings us together, and without those values, and without those people — the government-to-the government relationships are critically important — but they are somewhat hollow. They are somewhat hollow, if you don’t have the people fully connected. We are lucky that South Asians in the United States and India and the United States are really connected with shared values. So you ask about what we can do. I don’t think this is a one-way ticket. This isn’t about what can American companies do in India. I look at the great promise, for example, again this tragedy of Covid, I look at what’s happening in joint vaccine, research and discovery, I look at what we could do from a global health security standpoint between our industries, between our scientists, between our research laboratories. Yes, the government can help steer that a little bit, but ultimately that will be up to individuals and institutions in the private sector, civil society and academic sector. I look at climate change and I look at the impact on particularly a place like Bangladesh and parts of India, and the water shortages. We are impacted from climate change in a real way. That’s why India went into the Paris Climate Agreement the way it did, negotiated a very important deal. That’s why the United States was in. But ultimately the work on moving to renewable [energy], meeting those aggressive targets, those are done by the private sector. I look at the infrastructure needs in India, the massive urbanization taking place, the building of airports, high-speed rail, the building of smart cities — those are all things that are going to be done, not by governments. Those are going to be done by private sector, by private industry. And again, if you look at our economy, we need the greatest kind of Indian companies, Indian entrepreneurs coming here. That’s why I’m so concerned about this discouragement, or disinterest in having some of the best and the brightest come here. Also I’m concerned about removing family-based immigration. My family would not have made it here. I certainly would not have been able to go back 50 years later to represent the United States in India but for family-based immigration policies. That’s humane, that is just, that is consistent with the social compact of America. You work hard, you play by the rules. The next generation can do just a little bit better.

You aim high work hard and pursue your dream. How do you describe the U.S.-India relationship from the time you were our ambassador to India and now? Do you believe the U.S.-India relationship has the bipartisan support, which was not true even a decade ago? Do you believe that India relationship under the Biden administration will reach the next height and we will strengthen broaden and deepen our engagement with India based on the shared interest and share values?

I think it’s bipartisan. In fact, I would almost say U.S.-India relations is a non-partisan issue. I think everyone understands how important it is, but I as I said earlier I’ve been disappointed by the kind of transactional nature of the last three and a half years. I think the photo ops are important but they are not sufficient. And again I think about what’s happened to the denigration of minorities. I worry about that a lot and I worry about some of the strategic choices. The foreign minister of India talks about strategic choices. I think both India and the United States have to make strategic choices that bring us closer together. We can’t just assume that our kind of 18-, 19-year upward trajectory in the relationship just continues on its own. We have to make those choices that actually bring us together. Now look neither country aspires to have a military alliance. That’s not what we’re talking about. But we are talking about something built for this century, not for the last century. And you asked me about Vice President Biden. I was with Vice President Biden in 2006, in the Senate, when he said this, he said: “If in 2020, the two closest partners and friends in the world are India and the United States, then the world will be a safer place.” He made that prediction 15 years ago. So I know that this will be a focus for him going forward. He understands how important the relationship is. And it won’t just happen. It won’t just go up on its own. It will require a lot of work and a lot of dedication, and I think you’ll see that from him.

You mentioned the military alliance with the U.S. As you know India has no interest in joining a military alliance, but they need the alliance, I believe, against China. And India remains a close partner with [Russia]. Can you shed some light on this? Does that make a difference to America’s long-term strategy in terms of Indo- Pacific region?

I think not only does India not want a military alliance. The United States does not want a formal military alliance. And the reality is we haven’t entered into a military alliance in decades with anyone. The alliances we entered into were post-World War II architecture. They were the right agreements at the right time to keep the peace in Europe, to keep the peace in the Indo-Pacific. What we need now is something much more agile that takes into account all the elements of our cooperation — not just military. The military component is very important. Just take India for an example. We need full-scale cooperation militarily [and] economically. That means maybe doing a trade agreement, a bilateral investment treaty. That means having cooperation on climate, on global health, on immigration. We need a clear set of agreements on students, in higher education, on space cooperation, on research about the oceans. Frank, I could go on and on. My point is we need something comprehensive that creates a stickiness, a glue between us, where even if some leader wanted to shake us apart, that person regardless of party, couldn’t do it. Because we were so interlinked in so many ways. That’s what a modern alliance looks like. In fact, I’ll use the words of Prime Minister Modi and previous BJP leaders when they called us natural allies. Natural allies means we take all the elements of our cooperation, we put it together and we built something very, very strong.

Watch the full interview:

1 Comment

Very good Interview by Frank Sir .