Interview with author of Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World.

By Sujeet Rajan

NEW YORK: Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World (Cambridge University Press, paperback, $39.99, 355 pages) by Ritu Gairola Khanduri, a cultural anthropologist and historian, and an associate professor at the University of Texas at Arlington, is a superbly researched and written book, replete with fascinating, treasure trove of illustrations that will keep readers riveted.

The rare book will surely stand the test of time for decades to come. It’s an invaluable resource for anyone remotely interested in the subject of cartoons and cartooning in India.

Academic books often get lost in its own little world; may sometimes seem as heavy as listening to some of the speeches at the United Nations, benumbed by legal or scientific presentations — the in-depth zeal for niche subjects often overwhelm the average general reader.

Not so Khanduri’s book.

Khanduri traces succinctly the history of cartoons and the life of cartoonists and their pet subjects not by just poring through existing databases and archives on the subject in libraries in the US or India — which she does too, of course — by traversing through the country, meeting some of the veteran cartoonists, interviewing them, getting to know them. The cartoonists in turn, as reticent and shy of publicity as they have been in their lives, open up to her. She analyzes their work and the work of their peers with easy authority.

The result is a thoroughly enjoyable, lucid and wonderfully curated book which gives an immensely satisfying look and perspective into the history of cartooning and cartoonists in India, and much more.

In an e-mail interview to The American Bazaar, Khanduri (FB author page; Twitter), who read history at the University of Delhi and Jawaharlal Nehru University, and obtained her doctoral degree in anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin, refutes a question that the present India is an “age of gradual curbs on freedom of expression.” She maintains instead that cartoons have become overburdened.

Khanduri reveals that during her research and conversations with cartoonists in India, she sensed both despair and confidence in the future of cartooning and its continuing significance.

Excerpts from the interview with Ritu Gairola Khanduri:

In the 150 years of cartoons in India, cartoonists have had rich material to work on. As you write, the cartoonists’ fascination with the “slippery slope of life in India” is perhaps tempered with their “interpretative dilemmas and sensory effects and the meanings people make”. In the age of gradual curbs on freedom of expression, in India, are cartoonists relevant anymore?

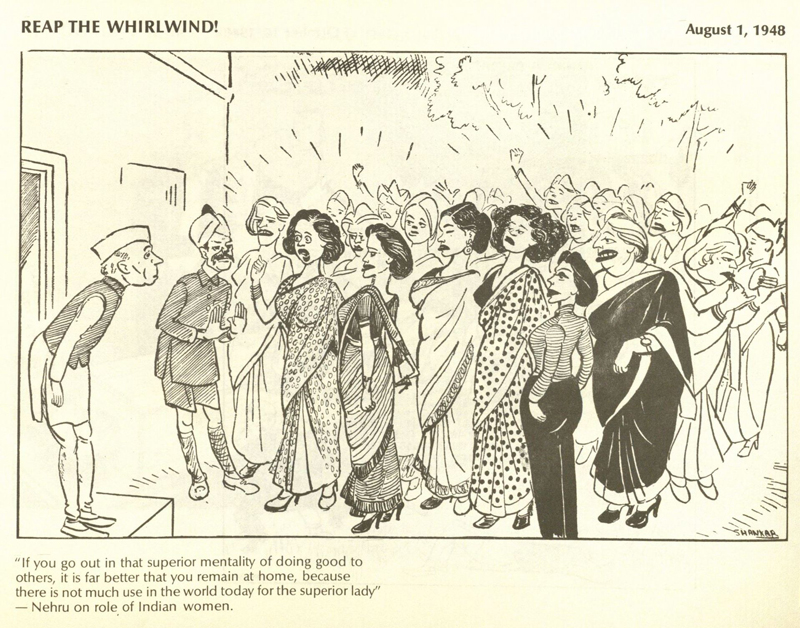

This is a very interesting time for cartoons in India, and around the world too. In India cartoons are important enough to demand the President’s attention. The theme of the President of India’s address on National Press Day, November 16, 2015, was caricatures and cartoons as a medium of expression of public opinion. In India we’ve seen a flurry of activity around the censorship of cartoons. Cartoons have become a busier turf for asserting state power as well as for resisting it. In my book, I have traced a longer history of interpretive claims, which are staged to question the appropriateness of the cartoon. Such questions in the form of petitions to the Press Council of India and letters to the editor are initiated by individuals of various political persuasions. I also discussed the 2012 NCERT controversy that embroiled the parliament and politicians of all stripes in a debate about Shankar Pillai’s 1949 cartoon depicting Nehru and Ambedkar, and the making of the Indian constitution. Soon after the NCERT issue calmed down, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was hauled up, and eventually acquitted, on charges of sedition, disrespecting national symbols, and inciting unrest. The Maharashtra police evoked colonial laws and newer post-colonial laws in their charges against Trivedi’s cartoon campaign on corruption in India. I would not mark this as an “age of gradual curbs on freedom of expression.” Cartoons have become overburdened. They now carry the weight of political truth that far exceeds expectations from prose and photographs in newspapers. This is the dual burden of cartoons in our times. Attempts at any curbs generate more cartoons and stirs debate.

It is far too simplistic and even inaccurate to presume restrictions on cartoons are a natural facet of conservative politics. It would be fair to say that we are in a new time for cartoons, one that is different from the time of the front-page cartoons. But that shrinking of space on page-1 doesn’t make cartoons irrelevant. During my research and conversations with cartoonists in India, I sensed both, despair and confidence in the future of cartooning and its continuing significance. The despair is spurred by the disappearance of the large front-page cartoons that once graced every prominent newspaper in India. The confidence in cartoons grows from their proliferation as “pocket cartoons” and circulation bolstered through social media. Adhwaryu’s, Manjul’s and Satish Acharya’s Twitter handles are good examples.

India has had its share of cartoons coming out in a publications, like the indigenous Punch, Baijnath’s Kedia’s Vyang Chitraval, Milli Gazette and Shankar’s Weekly – which folded in 1975. But India surprisingly doesn’t have a New Yorker type magazine or publication, with cartoons not only giving relief but as an instrument to reach out to the intellectual masses. Why is that?

Cartoons, like any cultural form that has struck roots globally, have distinct histories in each place. For example, while the pocket cartoon has a vibrant presence in India, it doesn’t in the US. The kind of intellectual work, you seem to point for the New Yorker, is done every day in India by newspapers in various languages, including English-language newspapers. R. K. Laxman’s pocket cartoon “You Said It” is a fine example of the pathos of city life, which translated across regions and languages — it made sense in Mumbai, Delhi, Kanpur and Bangalore, to name a few places. I believe this could be time, again, for a cartoon-based publication like the vernacular Punchs and Shankar’s Weekly. However, the English language does not reflect nor completely convey India’s intellectual landscape.

Taboo subjects like race issues have proved to be both a means to gain instant fame, or notoriety and fall from grace. Even in the US. Just writing about Trayvon Martin as a “colored boy” led to the firing of a cartoonist at the Daily Texan. But what is the point of a cartoonist taking only mundane subjects? Is India a land of only political cartoons at the best, especially in the 21st century?

A visit to Mumbai during Diwali is a good time to see the plethora of cartoons in the special Diwali number of various magazines. These are not political cartoons. But it is true we don’t have a Mario Miranda or Gopi Gajwani or Raobail or Manjula Padmanabhan in these times. I must add that admirable work is being done with graphic novels in India.

One would imagine that to take on, and even stymie the rise of the fundamentalist right in India, to curb the growth of organizations like the VHP and the RSS, writers and cartoonists would begin a vociferous tirade of sorts to kindle the ire of the masses against all forms of unfairness and brutality in society, including the lynching in Dadri, the stupidity of putting curbs and jail time, and death, for eating beef. But writers are giving back their awards to the Sahitya Akademi, and cartoonists refuse to take on the establishment. Will this change in India?

The lynching in Dadri has been condemned widely. The politics of beef is not new for India. The unfortunate Dadri incident brought those politics and absurdities to surface in an unprecedented manner. It revealed the paradox in India’s beef politics and got people talking and thinking.

Unfairness and brutality comes in all political stripes. Social violence is not unique to India. We can’t expect a cartoonist or two to counter an entire system — it is a collective responsibility. Authors and cartoonists lose credibility when they choose to be silent as a political convenience. As public intellectuals they have chosen an inconvenient life and they need to live up to it collectively. This holds true for academics too. It is a constant struggle in the classroom and outside the classroom — every time justice is discussed. But this notion of freedom — one that was lost — is a mirage. When were we free? Where were we free? So the question is what could free us?

Public demands on us will change the nature of our work. We will soon find it inadequate and even impossible to be a credible author, cartoonist and academic without publicly engaging a politics of justice. Those demands are not placed on us now. In fact a neutral stance is appreciated as one that signals a deliberated perspective. A leading cartoonist I recently met told me about “equal opportunity cartooning” — I found this interesting.

We have cartoonists of courage who can circumvent editorial clout and even free themselves of a newspaper’s platform. If we are not willing to respond to social injustice then we should, and perhaps will be, forced out of this world of writing, cartooning and teaching. So the short answer: Yes, I think this will change in India, and more widely too.

R K Laxman and Shankar Pillai had their protégé, whom they trained. But Kutty and Bireshwar didn’t, as you write. Today, most youth in India might not know the difference between a cartoon and an illustration. Is cartooning a dying art in India?

No. Cartooning is not a dying art in India. This is a good time for cartooning. I think it’s an art form the youth will give new shape to in the coming years. They also have a rich history in India to look back to and build on. The Institute for Indian Cartoonists (IIC) in Bangalore and the new cartoon museum in the Symbiosis Institute in Pune, are just the beginning of efforts to archive and promote cartooning in India.

You write “Abu’s cartoons during the infamous Emergency years are celebrated as some of the few embers that continued to glow against the paradox of a dictatorship in a democracy.” Do cartoonists in India have the temerity to take on prime minister Narendra Modi if atrocities against minorities continue to grow in India? More importantly, will newspapers have the courage to do so?

I think prime minister Narendra Modi and his predecessor, Dr. Manmohan Singh, have been at the receiving end of biting cartoons. Here are a few samples:

Satish Acharya on Modi;

Another Satish Acharya cartoon on Modi

An unsigned cartoon in the Tamil Vinavu.com

Shaunak on BJP’s loss in Bihar elections

Just like race issues, religion is a subject that is taboo, in India. In 1983, a complaint was lodged against The Times of India newspaper for depicting Lord Buddha in a pitiable condition. Atrocities are being committed in the name of religion in India, so should cartoonists not take on the subject of religion in India?

Cartoonists must take on issues that matter. They are our in-house critics and we can disagree and debate them. Cartoons on religion sparks sterner reactions thus the risk of caricaturing religion. Cartoons on the subject provoke people in India, and elsewhere too. Take a look at this link and Texas governor Abbot’s response:

India is a pluralistic society, a democracy, and freedom of expression for all purposes is still intact, though eroding. But India is also the country that was the first to ban The Satanic Verses, and the then prime minister Manmohan Singh protested against the depiction of Prophet Muhammad in Danish cartoons. Rushdie was not even allowed to read out from his book at the Jaipur Literature Festival. Did cartoonists in India take on these subjects when it came up?

The caricaturing of Prophet Mohammad is about more than the cartoonist’s freedom of expression. I have written about this in my book and elsewhere. It is fair to ask: why is the periodic caricaturing of Prophet Mohammad necessary for people in the west to pat themselves about their freedoms?

Here is a link to a cartoon on censoring the folk singer Kovan for an anti-Jayalalitha song:

http://breadcrumbstoons.tumblr.com/post/132284540510/poet-activist-s-kovan-was-slapped-with-sedition

Even in the land of a million political cartoons, protests had also come up when a cartoon depicted Sonia Gandhi as Mother Mary. Are certain politicians off limits for cartoonists in India?

That protest did not come up because Sonia Gandhi was caricatured. She is not off limits for cartoonists. In fact she is widely caricatured. The issue was that the Congress chairperson Sonia Gandhi and then prime minister Manmohan Singh were caricatured as Mother Mary and the infant Jesus.

Rushdie had predicted that India’s democracy would become a laughing stock. What do you think?

Rushdie was quick to judge.

R K Laxman or Shankar? Who is your favorite cartoonist? Or is it somebody like Mario Miranda, who most consider also as an artist for his cartoons?

Mario’s cartoons require a pause to admire his lines and composition. I felt the same way when I saw RK Laxman’s and David Low’s originals. The composition draws one in. Much of that that magic is lost when the cartoon is shrunk and reproduced in the newspaper. It is difficult to pick a favorite cartoonist. Much like a thali served with several items on it, a bit of pickle and peppers, I savor cartoons of all styles.

Which cartoonist from India would have made it big in the West, especially in the US, or is there somebody now who is waiting to emerge as the next Laxman or Sudhir Tailang or Shankar?

Abu, Laxman, Dar, Puri — all have worked with or received invitations from newspapers in the West. This is a different time. Indeed, Laxman and Shankar reigned supreme during their career. They were in good company with Samuel, Mario, Kutty, Bireshwar, Kaak and many others known to niche audiences. Now too we have a constellation of talented cartoonists but with a longer reach. They don’t have to depend on a newspaper as their sole platform.

(Sujeet Rajan is Editor-in-Chief, The American Bazaar. Follow him @SujeetRajan1)