The United States’ trade surplus with other countries on services increased roughly 400 percent over the past 13 years.

With the United States announcing tariff on a number of Chinese commodities and China responding with similar measures against US goods, the world seems to be moving away from the path of multilateralism, and into the era of trade wars and neo-mercantilism. Never before have such tariff escalations happened since the Great Depression, when the United States brought in the Smoot-Hawley tariff to give protection to its domestic industry, and other economies followed the suit, resulting in the ushering in of the beggar-thy-neighbor economic policies worldwide.

Is the current external payment situation of the United States so bad as to warrant the extremely provocative tariff announcements that President Trump is making via Twitter on a weekly basis?

Or is it simply a matter of the United States, which has the reserve currency of the world, trying to make an issue out of a non-issue by citing its current account deficit?

Let us see what the data released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), a US government agency within the Department of Commerce, has to say in this regard.

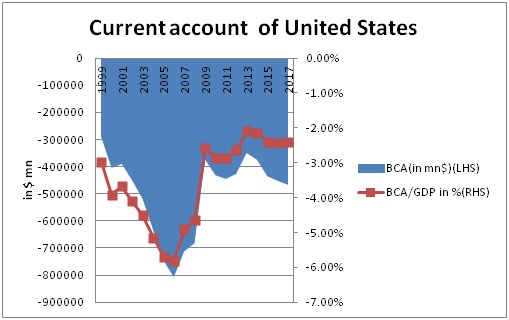

According to the BEA, as illustrated in the chart above, in the period prior to the global financial crisis in 2006, the current account deficit of the United States reached an all time high of $805 billion, amounting to approximately 5.86 percent of its GDP. The steepest increase in current account deficit occurred in the period between 1999 and 2006, when it literally quadrupled from $200 billion to $800 billion.

The proliferation of financial innovations, coupled with a rising credit to GDP ratio, bolstered household spending and also resulted in a steady rise in investment spending. This served as source of demand for the Asian economies, as well as the Germany, and at the same time resulted in reasonable amount of price stability within United States.

The favorable liquidity conditions of the period increased the leverage of the households and businesses to such an extent — and the process of securitization made it even more easy — that ultimately, with property prices falling, it proved to be recipe for disaster, culminating in the global financial crisis of 2007.

The current account deficit, which peaked in 2006, went down to $372.5 billion in 2009, before marginally increasing to $466.2 billion in 2017. At this level, the current account deficit is just 2.4 percent of the US GDP, which is far lower than any of the years between 1999 and 2010, when it was consistently higher than 3 percent.

This clearly implies that President Trump is trying to extent the domestic populist rhetoric to the international arena, without any rationale, in order to score some brownie points.

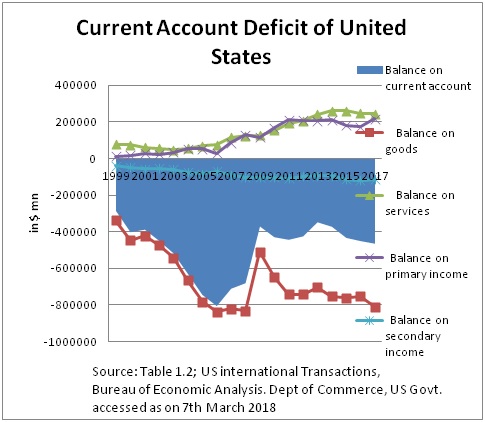

Trump is now threatening tariff by citing the $750 billion deficit, which is, in fact, not current account deficit, but the merchandise trade deficit of the United States in 2016. He is trying to use bilateral merchandise trade deficits with countries as the stick to attack trading partners, even though it is well known that both on the balance on services and on primary income, the United States has a surplus, not just with the rest of the world, but also with most of the countries at the bilateral level.

In fact, the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competiveness Act heavily relies on the size of US bilateral merchandise trade deficit with other countries to initiate trade sanctions and restrictions against them, gleefully pretending ignorance of the growing servitization of the world economy.

The pundits at the Office of the US Trade Representatives also act as if they are blissfully unaware of the fact that the production of commodities in the global economy is happening as part of the global value chain, and bilateral trade deficit with certain countries would automatically be a result of such an organization of production. Intra-firm trade constitutes a large share of the total merchandise trade worldwide. The growing investment incomes from abroad (more than $900 billion in 2017) would not have occurred without this merchandise deficit.

Let us take a look at Trump’s “$750 billion” deficit argument. The amount is the merchandise trade deficit of the United States in 2016 — not the current account deficit, as pointed out earlier. It should be noted that the United States had a surplus both on account of services as well as on investment account to the tune of $247 billion and $173 billion, respectively.

In the secondary income account, though, the country had a deficit of $120 billion, bringing the overall current account deficit to $451.6 billion. For all the trade injunctions which the United States would like to impose on the world, it should remind itself of the fact that its surplus on the services front has increased consistently over a long period of time.

The US surplus on services has increased from $75 billion in 2006 to $242.7 billion in 2017. In a little over a decade — the surplus was around $50 billion to $60 billion before 2005 — the US surplus has multiplied by five times. And this has happened at a time when international economic conditions were not that favorable.

There are very few countries in the world that has surplus on the invisibles income, other than the United States. (India is another country that has).

So Trump should tread cautiously, as retaliations on the services front, through blocking market access, would prove to be damaging for the United States.

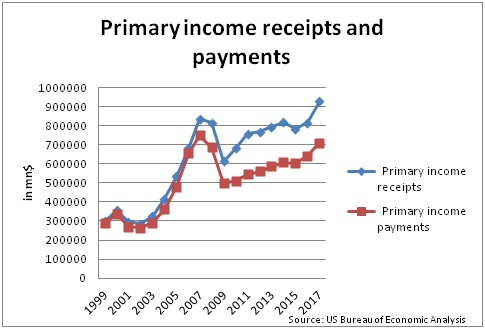

There has also been a consistent increase in surplus on the primary income front, which is the net earnings of US investments abroad. The surplus on this account has increased from $11 billion in 1999 and $53 billion in 2004 to $216 billion in 2017.

While US earnings on the primary account front and payments outflow on this account was $927 billion and $710 billion, respectively, in 2017, it was $680 billion and $653 billion, respectively, in 2006. The difference between primary income inflow and outflow has become larger both in absolute terms as well as in terms of GDP. See the chart below.

This further gives credence to the argument of a number of researchers worldwide that even when the United States has a current account deficit and it has been financed by net liabilities, attracted from the rest of the world, the net international investment position of the country has not deteriorated by as much, as these deficits have cumulated over the years. This is also due to the fact that far higher returns have been accruing to the United States on investments done abroad than to foreigners on their investment in the United States.

And, most importantly, the United States has a reserve currency, which is an exorbitant privilege. But with such a privilege also come duties and responsibilities.

If the United States wants to continue to have the privilege of having its currency the currency of the world, it cannot shirk away from its responsibilities. A time will come when the world will call Trump’s bluff.

(Krishnakumar S. teaches economics at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, India.)

More from Krishnakumar S.:

US intransigence led to collapse of WTO’s Buenos Aires ministerial (December 27, 2017)

Demonetization’s 14 trillion rupee question: will government get any money? (December 17, 2016)

India’s war on black money likely to result in a big bonanza for government (November 10, 2016)

With Brexit, is it going to be a season of referendums in Europe? (June 24, 2016)

Raghuram Rajan’s exit provides more fodder to the volatile financial markets (June 20, 2016)

Will writings based on Gods and Goddesses continue in India? (October 21, 2015)

Yanis Varoufakis is Keynes of our generation (July 7, 2015)

Will Modi’s plan to channelize gold holdings from temples to banking system succeed? (May 8, 2015)

All eyes on Yellen, as global markets brace for reversal in US monetary policy (March 21, 2015)

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank – Are the Bretton Wood twins being dislodged? (March 17, 2015)

Are the political duopolists in New Delhi colluding? (December 19, 2012)